:focal(715x483:716x484)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/54/1f548caf-5197-4904-a43c-4e25b2cf33a8/tombs.jpg)

Archaeologists were digging ahead of planned construction in Israel’s Negev desert when they came across several human-made piles of stone. They thought the piles were “tumuli,” mounds of earth used in Bronze Age burials that are found frequently in the area.

They quickly realized they were wrong.

This Ancient Greek Town Suffered the Same Fate as Pompeii

“As we kept digging, we understood that this was not something so common, but something from a later period and much larger,” excavation leader Martin David Pasternak, an archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), tells Ariel David of Haaretz.

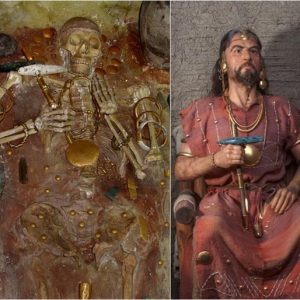

More than 50 skeletons have been uncovered in a unique burial site in the Negev, according to a study published last month in Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. The remains—which are roughly 2,500 years old—were found within two burial chambers separated by a courtyard.

“These kinds of tombs have never been discovered in the region until now, and they are not associated with any kind of settlement,” says IAA archaeologist Tali Erickson-Gini, who co-authored the study with Pasternak, to Live Science’s Kiley Price.

The researchers don’t know for sure why these bodies were buried at this particular site, but they have theories: The tomb lies at the crossroads of two trading routes that ran from Egypt through the Negev to southern Jordan and the Arabian Peninsula, and some groups considered these kinds of crossroads to have religious significance.

The bodies may have been buried on separate occasions over the course of many years. As Pasternak tells Haaretz, some of the skeletons were neatly laid out, while others were tossed into piles—a finding that’s typical of burial sites that were reopened several times, as older bodies were moved to the side to make space for newer ones.

The researchers think that most of these individuals were women, though additional analysis is still in process. In the meantime, the artifacts found in the tomb support this conclusion: While similar sites often contain weapons, this one held only two arrowheads. But it contained a much larger trove of jewelry, including bracelets, beads, rings, pendants and more, per Haaretz.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cc/c3/ccc3a5b4-cdbe-4773-9ecd-e532d236660b/tkvrjldbnexapafz4rrsgb.jpeg)

The artifacts at the site also “represent a salad of cultures,” says Pasternak to Haaretz. For example, the excavations revealed alabaster vessels and incense burners that were typical of southern Arabia.

The researchers theorize that these women could have been enslaved individuals who were being trafficked to Arabia, a practice that ancient written sources have described. “Many of these artifacts may have ended in the hands of women who were indeed coming from Arabia, but we think there is enough historical evidence to suspect these were foreign women who were being taken to Arabia,” Erickson-Gini tells Haaretz.

The discovery could provide archaeologists with meaningful insights into the region’s broader historical arc. “This excavation is vastly expanding our knowledge about this ancient trade network,” says Juan Manuel Tebes, a historian at the Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina who wasn’t involved in the study, to Live Science.

“We know a lot about the trade between southern Arabia and the southern Levant during the mid-first millennium B.C.E.,” he adds. “But most of our evidence still comes from the written record, particularly from sources of Greco-Roman times that date much later than this burial.”

Excavations originally took place ahead of a planned pipeline—but Haaretz reports that now, in light of the new discovery, the site will be preserved so archaeologists can continue their analysis.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.