The child – seen here in these remarkable pictures for the first time – appears to be from a higher social strata that previous remains unearthed at the site, the mysterious Zeleny Yar necropolis. Picture: Yamalo-Nenets regional Museum and Exhibition Complex

Scientists this week opened the mummified child’s remains cocooned in birch bark and copper which – combined with the permafrost – produced an accidental mummification.

The child – seen here in these remarkable pictures for the first time – appears to be from a higher social strata that previous remains unearthed at the site, the mysterious Zeleny Yar necropolis, close to the Siberian Arctic, which had ancient links to Persia. So far only one female – a child – has been found at the burial place.

The major new find close to Salekhard is seen as exciting by experts who are conducting MRI scans on the remains.

Alexander Gusev, research fellow at the Centre for the Study of the Arctic, told The Siberian Times: ‘We did the MRI scan first and yesterday held the first stage of opening the cocoon. We saw that the body was almost fully mummified, thanks to copper – or bronze – plates, except for the right hand and his legs.’

He said: ‘The remains belong to a boy, 6-to-7 years old. We suppose it was a boy because we have found small bronze axe with the body, and some sharp tool, which we can not identify yet.

‘The body was wrapped in two layers of fur, one layer is reindeer hide, with long and stiff hair. The other layer is softer, we will be able to say more clearly which animal it was after the analysis in Ekaterinburg.’

Along with the remains – the preservation of which was aided by permafrost – scientists found ‘a bronze pendant in the form of a bear’. Additionally, there was a ‘small bronze axe, and temple rings made of bronze.

The body was covered with copper or bronze plates on the face, chest, abdomen, groin – and bonded with leather cords.’ The items found with the body – the axe, pendant and rings – suggests ‘this was not some poor boy’. The child warrior was ‘not from the lower strata of society’.

It is early in their research and the experts say it ‘premature’ to know if the boy was from the most elite echelons of a society that appears different to others known in northern Siberia. Yet his method of burial also appears different to previous remains unearthed in this remote spot, where no adult females have been located.

Archeologist Natalia Fyodorova said: ‘We have not completed the works with this find yet, so we hope to find new details and a clearer picture soon. For now I can say that in the basis of this burial is some oval wooden structure, resembling the big oval plate. We will know what is this more exactly after finish our work.

‘On this plate lies the body of a boy wrapped in some soft fur….over the fur layer lay the bronze things – axe, pendant, rings and metal plates. Then it was covered in the second layer of fur. Next it was overlain with bast and then all wrapped in the bark.’

Dr Fyodorova, deputy director of the Shemanovsky Science Museum and Exhibition Centre, said: ‘If we compare this with previous child burials on this site, we can see some things in common. For example, all the children were wrapped in fur and had no other clothes.

‘Still, this burial differs. First of all, other children were buried in a wooden sarcophagus, but here we some some oval wooden construction. The other difference is that here we can see many things buried with this child – axe, pendant, bronze rings. It is not typical.

‘At the moment, a second MRI scan is underway to detect more details.’

Scientists say the mummification at this site was ‘accidental’: it was not intended by this ancient clan, but happened because of the copper and permafrost. The boy’s remains were dug up several weeks ago, but only now opened in Salekhard. It is the first mummy from the civilisation found at this intriguing site since 2002.

‘The birch bark ‘cocoon’ is of 1.28 metres in length and about 30 cm at the widest part’, said Dr Gusev. ‘It follows the contours of the human body.’ Iniitally they suspected a teenagers remains lay inside the birch bark, but when opened it is clear the child is much younger.

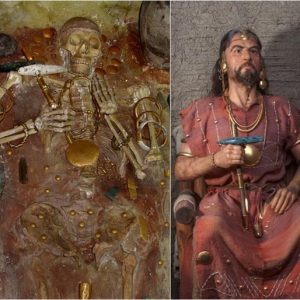

Previously, archeologists found 34 shallow graves at the medieval site, including 11 bodies with shattered or missing skulls, and smashed skeletons. Five mummies were found to be shrouded in copper, while also elaborately covered in reindeer, beaver, wolverine or bear fur. Among the graves found so far is just one female, a child, her face masked by copper plates. There are no adult women.

Five mummies were found to be shrouded in copper, while also elaborately covered in reindeer, beaver, wolverine or bear fur. Pictures: The SIberian Times, Natalya Fyodorova

Nearby were found three copper masked infant mummies – all males. They were bound in four or five copper hoops, several centimetres wide.

Similarly, a red-haired man was found, protected from chest to foot by copper plating. In his resting place, was an iron hatchet, furs, and a head buckle made of bronze depicting a bear.

The feet of the deceased are all pointing towards the Gorny Poluy River, a fact which is seen as having religious significance. The burial rituals are unknown to experts.

Artifacts included bronze bowls originating in Persia, some 3,700 miles to the south-west, dating from the tenth or eleventh centuries. One of the burials dates to 1282, according to a study of tree rings, while others are believed to be older.

The researchers found by one of the adult mummies an iron combat knife, silver medallion and a bronze bird figurine. These are understood to date from the seventh to the ninth centuries.

Unlike other burial sites in Siberia, for example in the permafrost of the Altai Mountains, or those of the Egyptian pharaohs, the purpose did not seem to be to mummify the remains, hence the claim that their preservation until modern times was an accident.

Similarly, a red-haired man was found, protected from chest to foot by copper plating. In his resting place, was an iron hatchet, furs, and a head buckle made of bronze depicting a bear. Pictures: Kate Baklitskaya, Go East

The soil in this spot is sandy and not permanently frozen. A combination of the use of copper, which prevented oxidation, and a sinking of the temperature in the 14th century, is behind the good condition of the remains today.

Dr Fyodorova, of the Ural branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said previously: ‘Nowhere in the world are there so many mummified remains found outside the permafrost or the marshes.

‘It is a unique archaeological site. We are pioneers in everything from taking away the object of sandy soil (which has not been done previously) and ending with the possibility of further research.’

In 2002, archeologists were forced to halt work at the site due to objections by locals on the Yamal peninsula, a land of reindeer and energy riches known to locals as ‘the end of the earth’.